selected and appraised by winners of the Awards in the previous issue.

|

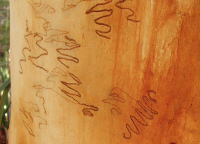

Several species of eucalypts (gums) exhibit distinctive squiggles that

result from moth larvae eating the live wood and leaving a scar that

is revealed when the tree sheds its bark. This image of a gum

with its insect-generated calligraphy, inspired the naming of the award.

|

AWARD RECIPIENTS

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

Ross Clark

an appraisal by Dorothy McLaughlin

how old is the airThis tanka is about things invisible and intangible, air, memories, dreams. The lake and air bubbles on the surface are present, a concrete start for the poem, but even they don't have shape and get their color from other matter. As water and air are essential to life, so memories of what was and dreams of what might be are necessities for our souls.

that bubbles to the surface

of the lake? how old

are my memories my dreams?

& who breathed them before me?

Ross Clark

Recently I read something, source forgotten, recalled by the tanka, about how the air we breathe may have been inhaled earlier by a genius. Interesting idea, I thought, happy to think of being connected to the past and future by air, in touch with those I love and strangers, the famous, the intellectuals, and all the rest.

The pivot was a repetition of the first words, "how old,"at the beginning of the first line and at the end of the third. He poses the question. His readers' answers, if they have any, will vary.

Then, the last lines held my attention. Memories shared? Well, of course. Even though we don't see events the same, we do share. However, my dreams are unique, aren't they? Not quite, according to Ross Clark. I pictured him standing alone at a lake, a slight haze blurring the surrounding green vegetation, before sunrise or just after sunset's glow has gone, aware of his place as part of a boundless community rather than of himself as individual.

Primarily, it was the tanka's message, its subject and substance, that caught me. After many readings, I was intrigued to notice the traditional 5/7/5/7/7 pattern, without thinking about the punctuation often considered part of the syllable count. Moreover, I liked the flow of the poem, one line to the next without hesitation. Teachers from my school days instructed us not to stop at the end of a line when reading or reciting poetry, rhyme or not, unless punctuation and sense called for a pause. The absence of a comma between "my memories" and "my dreams" impelled me on like thoughts crowding the mind or bubbles rising to the surface. Unlike those thin-shelled air bubbles, the poem stayed to keep me company, like the memory of a quiet lake.

Michael Thorley

an appraisal by Amelia Fielden

Fittingly, there appear in this inaugural issue of Eucalypt, five eucalypt, (or gum, as it is commonly called in Australia), tanka.

One of them, a lovely piece by Janice M. Bostok, introduces the journal with these appealing lines:

eucalypt leavesLater, amongst the pages of delightful tanka, I found this gem by Michael Thorley:

in stillness spin round

thin then broad –

eyes not yet open the pup

nuzzles into my hand

our front yard gumMy initial thought was ‘how Australian’, my second, ‘how fresh and unclichéd’. This is so down to earth in its sentiments, and yet it has that lightness of touch and expression which characterises skilful tanka.

grown from a sapling

to a giant –

all those black cockatoos

fair exchange for a lawn

The Australianness is not simply the setting with our unique black cockatoos. It is in the poet’s attitude of ‘fair exchange’: the barren ground which results from the gum tree using all available moisture to sustain its growth, is offset by his delight that this giant now attracts ‘all those black cockatoos’.

Australian, yes – but universally, too, this tanka can be read as affirming the positive acceptance of nature’s gifts over an artificial construct, a lawn. We can do without the extravagance of lawns, especially in these drought years in Australia; yet we do need wild birds, ‘the creatures of the air’, in our urban lives. For most of us, birds symbolise freedom, and grace in freedom. There is a balance in this tanka, birds for a lawn, and also the sense of life’s inevitable movement and change: sapling into giant tree, sown grass into rough ground, the coming and going of black cockatoos.

Thorley’s tanka is not only layered with interest and meaning, it is also technically sound, following a traditional short / long / short / long / long rhythm for a total of twenty-five syllables. The final two lines, of six syllables each, are beautifully balanced, and roll off the tongue.

Congratulations to the poet.

Kirsty Karkow

an appraisal by Michael Thorley

a snapshotHow fortunate we are that this particular “Eucalypt” flowers twice a year! How daunting, though, the task of choosing just one of the profusion of blossom-sprays for appreciation when so many draw one’s eye (and heart). How sad to have to bypass the wit, drama, sadness of so many to select just one. Anyway …

of me and the girl -

between us

handsome as ever

is my only son

Kirsty Karkow

I chose, after much deliberation, the tanka above. It only made its full impact on me on the second reading through the collection. I like it because of its tight construction, careful crafting, and unique subject – motherly love and possessiveness. It is also (I hesitate to use the term) multi-layered.

The basic situation presented to us is of a mother looking at a snapshot of, I guess, herself and “the girl”, with her son positioned between them. The attitude of the mother toward the two people is markedly different. The girl is just “the girl”, without name or status. The phrase places her at a – slightly wary, cold or hostile – distance. The son, on the other hand, is admired as “handsome as ever” and then revealed, in the last line, to be “her only son,” thus emphasizing his special value. The weight of her attention is on her son.

For me, this tanka centres on the close relationship that a mother can have with her son, and the wariness and guardedness that can accompany it, especially when a lover or potential partner approaches with designs. The phrase “between us,” aptly placed in the middle of the tanka, is the heart of it. Its first meaning is the simple one of physical location in the snapshot. I can see (or imagine) three other meanings of “between.” First, the son is someone that may be claimed by both mother and “the girl,” and hence the object of a struggle “between” them. Second, there is the possibility that the mother’s relationship with the girl will be mediated by the girl’s relationship with the son – “between” as “coming between” or “standing between.” Third, if we take the tanka slightly differently, and see the mother’s realization of the normality of what may occur between the son and the girl, but with the understanding that there will be, naturally, some pain for her, the “between” suggests “moving between.” This gives the tanka a feeling of sadness, rather than of possessiveness. These various meanings, if I have not gone too far astray, give the tanka a depth that unfolds only on closer reading.

The tanka is concise, with a neat 3-5-3-5-5 syllable rhythm. Each line adds something significant to the picture, culminating in the final line, which strongly underlies the son’s value to the mother, and reinforces the tension between herself and “the girl.” The tanka suggests that a real story is yet to unfold, a suggestiveness that adds to its strong impression.

A colleague of mine once commented that life is a series of separations, beginning with birth - when the child separates from the mother’s body. This tanka captures skillfully the tension inherent in another of them.

Editor's Note

Like Ross Clark, Michael Thorley found choosing one poem only, very challenging. Here are Michael’s comments on another of his favourite poems.

Moira Richards

my breastThis is a tanka with punch. It was one that gripped me immediately when I read through the collection the first time. As I see it, the person speaking has lost a breast to cancer. The dreadful, existential question that goes with such situations is: is this the end of it, or will the disease strike again, with similar or worse results? The breast is seen as an offering to an unseen killer, in the hope that this single, massive sacrifice will be all that is required. The mention of the Minotaur sent me to my references to refresh my memory of Greek mythology. This brief research provided evidence for the aptness of the metaphor. The reference to the Minotaur is deeper than might appear on a quick reading.

on the minotaur’s

altar …

will it be enough

to sate his hunger?

Moira Richards

The Minotaur, in mythology, was a monster with the head of a bull and the body of a man. He existed in the fabled labyrinth and, before being slain by Theseus, demanded human sacrifices from the citizens of Crete. The cancer is thus represented as a monstrous creature (very true), partly human, living in a treacherous labyrinth (as the body can be understood), and devouring the lives of a certain number of young people each year. The mention of the altar also brings in that helplessness and desperate supplication we can feel when confronted by life-threatening and unpredictable forces.

The tanka is in a concise and exact 2-5-2-5-5 syllable form, and reads naturally. The point is made directly and concisely. The use of the minotaur as a poetic embodiment of the cancer is apt and effective. Although it is not part of this tanka, we can extend the metaphor, and note, with a cheer, that the Minotaur was, eventually, slain.

Bob Lucky

an appraisal by Ross Clark

The anguish of the editor or the judge is akin to that of a child having to choose just one confection from a cornucopia; with these tanka, however, I could take a “suck it and see” approach repeatedly, without in any way diminishing the particular piece (in fact, they tasted better each time). Nevertheless, I eventually ended up with three mighty tanka, but then found myself choosing the one that had shone out on my very first reading of the issue: Bob Lucky’s “I’m trying to see”.

I would like to begin, however, by noting the pieces by Linda Jeannette Ward and Cynthia Rowe. Ward’s “peeling” tells a story of domestic continuity in a wry and warm fashion ~ her grandmother manages to retain a recipe secret even after her death. Rowe’s “rain has pounded” is a more public narrative of family ~ rain hides, and fire cannot find, the missing one. Both these tanka exhibit formal looseness, in that most lines are of similar length, the endings decided by the narratives. Each resonated in its own way.

Lucky’s tanka is also formally loose, just 21 syllables arranged fragmentarily (almost in four lines really), but charmingly just right.

I’m trying to seehe says, and we know the staying is not just of this moment, but most likely of this relationship. He is at a point of decision, and naturally either course of action produces regrets. If he stays there are plenty of negatives with the positives; if he goes, there are equally attractive positives accompanying the negatives of the broken relationship. Many of us can relate to this dilemma, too many of us.

the point of staying –

But "if I sit/ just so" Lucky continues, a little something happens that illuminates the moment, as it has many times in the past. Ironically, the source of illumination is that symbol of continuing inconstancy, Lady Luna. She is always there, revealing and hiding her face, month after month 13 unlucky times a year. Always waxing, always waning, the story of every relationship.

if I sitI rejoice in the audacity of that conjunction, as the fickle moon floats in the brief cup of tea, giving comfort and direction to Lucky as he contemplates what to do in the next moment and for the rest of his life.

just so the moon

floats in my tea

I’m trying to seeMay the moon always be with you, Bob, and with all of us.

the point of staying –

if I sit

just so the moon

floats in my tea.

Melissa Dixon

Appraisal by Kirsty Karkow

Beverley George has selected such excellent poetry for this collection that it is almost impossible to choose a favorite. There were roughly ten that I kept going back to, wondering which one would, or even could, separate itself from its elite companions. Gradually, I became aware that one poem followed me around. The words would repeat as I went through my daily routines and kept revealing new and deeper layers of meaning. Here it is:

tracking

black against the sky

an eagle's shadow

stay still . . . I whisper

to his small prey below

Melissa Dixon

From the first to the last, see how each word is essential and important creating multiple meanings? The first line is ambiguous. From there on, many interpretations evolve. And questions. We know the poet's emotional viewpoint but where is she actually standing?

It feels like a prayer from some-one who knows that any movement will reveal a secret or a hiding place. Sharp eyes from above (maybe even God's?), are watching! Be careful. Listen to the warning. Behave. Or else things are going to get rough.

There are many options but the feeling of alarm is central as poet and reader feel anxiety and sympathy for a mouse, a rabbit or even a fish. These feelings of identity with and concern for the underdog can be translated to other scenes. The bully in a schoolyard comes to mind, leading to any situation where an oppressor is about to take advantage of the small and meek. I think of the strong countries or tribes that have overwhelmed weaker nations. Let's not forget the various tracking devices used in modern warfare, and methods of extracting information. The caution is well advised.

Is life cruel? Yes. “Nature, red in tooth and claw” ( Alfred, Lord Tennyson) is how the world functions but, as sensitive humans we mourn any death and fear for any creature that is being stalked. We dread the thought of unwarranted punishment.

These are a few of the layers that pervade this simple verse making it quite special, in my view.

There others that shine with elegant yet deep simplicity. For instance:

before he leapsHere is a farmer who has lost his farm. He is desperate. A quarter of the farms have failed, or are struggling to remain viable. He can't sleep or see a way out other than suicide. Is it possible that even this can go wrong?

does he test the rope

around his neck

this one-in-four farmer

who can't sleep anymore?

Kathy Kituai

And, also:

near-drowning--The sharpness of life; the quiet of death. I grew up with the story of my Great-aunt Jessica's drowning and revival. She fell off an ocean liner. Apparently the breathing of cool sea water was pleasant compared to the pain of resuscitation.

I still remember

the silence

and then the sting

of salt water

Margaret Chula

There are many more poems most worthy of being chosen. I wish I could talk about them all.

Denis Garrison

an appraisal by Bob Lucky

I have to say those tanka by that Lucky fellow…. No, in all seriousness, this was the most pleasant and the most unenviable task I’ve had in some time. Beverley George, having done such an excellent job in compiling this issue, left me with too many choices. Not only were the tanka of a high quality, they were also of an amazing scope, ranging from the existential angst of contemplating one’s smallness in a potato field to the immediacy of drought, from death and disease to the gratitude for a dry loaf of bread and the excuse not to take a walk.

I read and reread. At one point, I thought it might be instructive to identify a stinker, one I really didn’t like, but failed to find one. Eventually about half a dozen “winners” lodged in my brain before two broke free and floated to the surface. I liked the way both Barbara Fisher’s “lying in bed” and Denis Garrison’s “in the long night” trip up the reader’s expectations of where they are going, but the poignancy and rhythm of Garrison’s piece finally won me over.

Garrison’s opening two lines are a risky ploy: two prepositional phrases crowned with clichés.

in the long nightThe repetition of grammatical structures is often effective in creating a rhythmic momentum, which I believe is the case here, and I responded positively to that. (He also uses repetition of grammatical structure in lines 3 and 4 to similar effect.) It also sets an interesting tone, as if we are about to hear a storyteller embark on an epic. However, the clichés confounded me. I was sure I was being set up, but not sure if it was for a joke or for a dose of maudlin spirituality. It was neither. Instead, Garrison strips the clichés of their moorings by taking away any chance of their resolution by the narrator. The night will be long and the grief dark for he is

in the darkness of grief

blind to hopejust those things we think would save the day, so to speak. Had they indeed been a source of solace to the narrator, as they can be to some people some times, the entire tanka would have gone down the drain of sentimentality.

and deaf to prayers

So, not deluded by hope or seduced by faith, Garrison focuses on the one thing that is real, the one thing he can hold on to: a hand. We don’t know whose hand, only that it is a hand that matters a great deal. And in the circumstances of this tanka, in the wording of the last line, it is just possible that the narrator is holding on tightly for his own sake. After all, there is a wonderful ambiguity here. Assuming it is a death-bed scene, it isn’t clear if the narrator is in the bed or beside it.

in the long nightIn five lines, Garrison has written an epic of sorts by capturing the unvarnished nature of mortality and our desire, despite all odds, to hold on to life, our own and that of those we love.

in the darkness of grief

blind to hope

and deaf to prayers

I hold tightly to your hand

James Rohrer

an appraisal by Melissa Dixon

I am honored to have the opportunity to choose a favorite poem from the elegant pages of Eucalypt, but, as with others before me, I found it difficult indeed to isolate just one from such a wealth of offerings!

As I studied the fine contributions in the last issue, over time I returned again and again to the compelling immediacy of James Rohrer’s poem:

never pity

the solitary bird –

what poetry

the owl must hear

in the wind, in the trees

The writer calls our close attention to a night owl silhouetted against the sky. In the first lines: “never pity / the solitary bird”, he warns. He notes with empathy the gifts of poetry an owl receives within its intimate nocturnal surroundings. Of course, the first impression for the reader-poet is a close connection with this owl! As poets, we are essentially eremitical: Consciously or unconsciously we see ourselves as a “solitary bird” — up late at night we craft and polish our own small songs. In the final three lines, through the use of graceful phrasing, Rohrer creates the eerie impression of an owl silently flitting from branch to branch – at home in the forest! Indeed — “never pity” us!

From a technical position, I searched for flaws in this poem, but must confess failure in this respect. There are no unnecessary words or syllables; every phrase nestles perfectly into place. The central pivot phrase, “what poetry” sits comfortably between the first two lines and the last two. In my opinion, this is a perfect little poem.

Annette Mineo

an appraisal by Denis Garrison

The cost of having your tanka selected for one of Eucalypt’s Distinctive Scribblings awards is having to try to choose one poem from the next issue—just one—as its outstanding tanka. I have found that a high cost, indeed, for Eucalypt 4 is full of outstanding poems. My first “short list” was half the issue! However, becoming increasingly cruel in my appraisals, I found some little nit to pick with many of the candidates. I finally came down to a true short list, which follows:

the peonies

hard pink fists

ready to open

and you pressed against me

this early morning hour

—Annette Mineo

this beach glass

scoured a cloudy blue

so like your eyes

fading and emptying

to a relentless tide

—Carole MacRury

past midnight

a robin’s alarm call

I turn

into the sliver of moonlight

stretched across the bed

—Maria Steyn

Annette Mineo’s “the peonies” is my selection. I cannot find a single nit to pick with either Carole’s or Maria’s tankas; they are truly wonderful. But . . . Annette’s has a power and beauty that puts it at the top of my list.

the peonies

hard pink fists

ready to open

and you pressed against me

this early morning hour

This tanka is an extraordinary exemplar of that “certain haziness” that characterizes tanka, despite its vivid imagery. The pellucid diction leads the reader to expect a definite image and that of the closed peonies is certainly vivid and accessible. Still, what is happening here? Ah, that is the magic of tanka: the reader must complete the poem. The deceptively plain statement conceals a myriad of possibilities; there is plenty of dreaming room for the readers’ individual experiences and contexts to fill with detail.

I have no idea if Annette had one specific scenario in mind for this tanka, nor what it might be if she did. As just one reader, my initial reading was in the context of an erotic encounter. In that context, the alternating texture of the lines, the incipient explosiveness of flowering, the visual imagery, the closeness, the time of day, all build towards a climax that is just beyond this moment. The tanka is gorgeous, intimate, powerful.

Of course, that is just one reading. Pondering upon the poem, I found myself looking at a very different scenario: a mother holding her new-born to her breast in the gentle dark before dawn. A classic mother-and-child image, even a Madonna and Child, is possible here. The power of the poem is undiminished, but shifts from eroticism to even greater intimacy, even purer love. Whose heart is so cold that this image does not warm it?

It also occurred to me that I am reading this tanka with a feminine persona assumed and that doing so is not at all necessitated by the poem itself. Even more variations open up.

I daresay some present readers of this appraisal are right now certain that I am a dunce or blind because they have readings completely different to any I have suggested. That is the magic of tanka in action! Annette Mineo has given us a tanka in which not one letter may be changed; it is fully realized and has amazing depth.

This is a tanka that I shall long remember and enjoy.

Lisa M Tesoriero

an appraisal by James R Rohrer

With so many outstanding poems in Eucalypt 5, how to select just one for distinction? Inevitably my choice will say as much about me as the poem I have selected. I especially enjoy spare tanka that effectively employ metre, assonance and alliteration to achieve a strongly lyrical quality. I look for a clear image that allows me to enter the scene easily, and I most resonate with poems that are deeply sensual. This is an admittedly difficult quality to define. Perhaps the novelist James Baldwin captured it best when he wrote that "to be sensual is to respect and rejoice in the force of life, of life itself, and to be present in all that one does, from the effort of loving to the breaking of the bread."

As I read and re-read Eucalypt 5, I found many wonderful tanka that fit this criteria. Cathy Drinkwater Better's fingertips, aglow with sunlight and throbbing with music. M. Kei's loss for words as he experiences the miracle of simply being alive to the beauty of creation, unable to communicate to a young son a spiritual reality that can only be known by direct intuition. Kirsty Karkow walking away from a seed, aware that she is only part of a generative process of life that will continue long after her act of planting has been accomplished. These, and many other poems, enriched and humbled me.

After several days two poems kept calling me back again and again. It is really impossible for me to say whether I am most affected by Mariko Kitakubo's lovely tanka of remembrance, where citron flavored noodles become a sacramental communion between a mother and daughter, or Lisa M. Tesoriero's footsteps in the sand. Since I am only allowed to select one tanka, I will choose Lisa's wonderfully expansive meditation.

Without directly stating a location, Lisa's opening three lines conjure up an image of a sandy strand. I envision it as an seaside beach; the vast expanse of the ocean, never mentioned, is nonetheless a powerful presence in this poem. She draws our attention to the countless footsteps of people who are walking along the shore with her, people of every age and kind. Humanity, on the edge of a vast creation.

Lisa's poem invites us to ponder with her our place in this vast sea of life. Perhaps the natural tendency is to find our own personal space of security, to mark off carefully what is ours, and to cling to this comfort zone. The struggle of the individual to protect his or her own selfhood over and against all others is surely a major component of human existence.

Lisa looks for her own footsteps in the sand, but finds it difficult. In light of the natural drive to individualisation, we might expect her to state the problem thus:

sometimes it's hard to know

which belong to me

But in the final line she instead inserts the crucial word don't, and the poem is transformed into a marvelous meditation on the impossibility of individual identity. We are inextricably a part of everyone else and everything else.

footsteps

of all sizes

on the sand –

sometimes it's hard to know

which don't belong to me

— Lisa M Tesoriero

Technically this tanka is well-crafted. The repetition of the "s" and "o" and the careful attention to metre creates a pleasing lyricism that begs to be read outloud. Thank you, Lisa, for sharing your poem with us.

John Martell

an appraisal by Annette Mineo

There is nothing easy about choosing just one poem to be honored above the rest, especially when choosing from a journal such as Eucalypt, filled with only the finest tanka from all over the world. Like others who have had the honor before me, I found it a most difficult task, compiling list after list until I was left with this one poem by John Martell that I could not resist:

all my lines

are tattered today

like poppy blossoms

blown against

this picket fence

— John Martell

The first thing that struck me about this poem was its easy, fluid rhythm, the lines just rolling off the tongue, falling in sync with the next until you have this one perfectly succinct simile, not a word or line out of place or unnecessary. Simple, clear and concise. I was also struck by the poem’s dramatic imagery—the poppy blossoms lying tattered, having been blown against the picket fence, an image as beautiful as it is tragic. There is a subtle irony at work. While the images speak of destruction and ruin, the poem itself unfolds smoothly and naturally, revealing a higher truth within five little lines. The end result is one of creation rather than destruction.

But while these things make John’s poem good, one thing in particular for me makes it great and that’s its first line. Upon my first reading, I interpreted “all my lines” to mean “written lines”—the poet is struggling to create a poem and everything he pens ends up tattered and useless, which he likens to the poppy blossoms. But after reading and re-reading the poem, I quickly came to see how there was actually a plethora of possibilities we could attach to this word “lines”. By basic definition, “lines” are connectors or pathways. “Lines” could be words, penned or spoken, a brief note or an insincere phrase. A “line” could be one’s gig or expertise or direction. It could signify a row, a crease, an outline or even a boundary. Symbolically, “lines” could mean all his efforts in the world, or perhaps his connections, with people, with God or with himself. The inferences are endless.

While I can’t say for sure what John meant in this first line, I can say that the meaning has been made larger than even he might have intended by his choice of words. If he had in fact used “words” or “poems” in place of “lines”, you can see how we would have had a very different poem, one not even half so rich or meaningful. But by using the phrase “all my lines”, John has infused the poem with nuances that go far beyond even our own understanding of what’s at work here. Everything within the poem and outside of the poem seems to come back to the word “lines”. Look for instance at the last line— what is a “picket fence” but a boundary or a border made up of a neat little row of “lines”? How brilliant! Poems are made up of lines as are our connections to others and our paths through life. Lines play many significant roles in our lives, and it isn’t always a bad thing for them to become broken or tattered or disconnected. But these “lines” of John’s are far from “tattered”; they result in a single lucid, flowing line rich with meaning.

For me, John has written the perfect tanka—a poem with natural rhythm, striking imagery, subtle irony and incredible depth of meaning. It is not just a poem of images or just a poem about an event or even an idea—it is a multi-layered poem that reveals a powerful message, reminding us all that even through imperfections in this life, it is possible to draw “lines,” or connection and meaning, to the earth, to the world around us and to one another—and this to me is what makes John Martell’s poem more than worthy of this award.

Maria Steyn

an appraisal by John Martell

Beauty is in the eye of the beholder is an old and now so trite maxim that we rarely think about it when we use it. It implies, of course, a subjective aesthetic judgment, despite various aesthetic schools which believe there must be a few objective criteria on which to base our judgment and discern good from bad art. In most ways, our judgment is always subjective and it is not a matter of great importance… unless, for example, you have 15-20 excellent poems in front of you and have to choose one. After five readings of Eucalypt, Issue 6, I found that even being as subjective as I could be, there were still too many excellent poems to choose from. So, in the end, I let my intuition sleep on it overnight and decided Maria Steyn’s poem, “deep autumn---” was the poem that had the strongest effect on me.

Briefly, it is beautifully written in the sense of being highly poetic, it has exquisite imagery, and a sense of mystery about it that can be suggested, but not directly stated. In particular instances she uses negatives in a powerful way as if the night is incomprehensible, a dark halo itself: her no, no, not, are wonderfully placed. And several of her lines have an assonance dear to my heart, e.g., “to stir the faint circle,” so pleasant and subtle. Finally, however, I was drawn into the circle of moonlight on the lawn. It is the kind of ethereal circle we observe from our window which draws us to the mystery of experience, of our standing in the world. We think there must be something quintessential here that has meaning, something that stirs us deeply, but ultimately faint, evasive.

In Maria’s poem she directs us to this experience but it is not itself said because we really cannot say it directly. We feel it, perceive it, words draw us toward it. Thus the poem takes us to the luminous edge, where a poem should take us and leaves us in awe of what the poem has conjured. When I read this poem for the final time, I recalled all the nights when I stood at my window gazing at the moonlight resonating in purple hues on the glowing expanse of snow below me—and I am touched by the unnamable stillness, the mystery of it all, seeing what I cannot say.

John Martell

Kirsty Karkow

an appraisal by L.M.Tesoriero

At the risk of parroting the words of previous judges, choosing one winner from over a hundred is a daunting task. I believe the poems found in Eucalypt 6 are outstanding examples of their form and I would go so far as to say their authors are among the best writers of tanka in English today. To judge them is a real honour.

Kirsty Karkow’s tanka was not initially on my short list, but further reading convinced me that it deserved to win. This poem deals firmly yet gently with serious and potentially inflammatory themes, and in the best ‘less is more’ tradition, we are not told what to think, but are left to ponder the ambiguities raised.

put aside

elections and talk of god

a searchlight

scans the rounded sky

hunting for one straight line © Kirsty Karkow

I have heard it said that one shouldn’t speak of politics and religion. This tanka has both in the second line. Not only that, but these ‘social unmentionables’ are presented in the form of a command. I’ve read very few tanka which commence by demanding our attention with an order –

“put aside

elections and talk of god”

Although Kirsty is telling us to ‘put aside’ these things, it automatically brings them to mind; our defences are raised, ready to react if necessary. My natural instinct when told what to do is rebel, perhaps even do the opposite, yet this tanka had me intrigued. Who is speaking? The author? And why say this? Reading further I discovered much more than anticipated.

Speaking of god and elections leads not only to circular arguments, but in the extreme, to war and death. To be able to ‘put aside’ these topics for a while may help create a safer world. Sure, continue the search but don’t expect to find ‘one straight line’ in a ‘rounded sky’.

Nature is made up of curves. Straight lines (and hope) belong to humans. I see Kirsty’s poem as being about humanity searching, looking upwards for proof and answers that possibly will never be found; for one simple answer to complex questions, such as those of politics and religion. It is human nature to hope that there is something looking after us: an honest politician, a party with an agenda for the betterment of all, an all-seeing, all-loving god. The searchlight scans and people hunt, yet they discover nothing. But the tanka does not suggest that we should give up our search.

Kirsty has crafted this tanka very skillfully. The syllable count creates a natural rhythm, each line leading to the next. There’s a major break after ‘god’; but there’s also a slight pause after ‘sky’. This feels natural, as if Kirsty is giving us time to take in the enormity of what she’s just said.

There are many other poems I feel deserve acknowledgement but I will limit myself to two from my short list. Personally, I love multi-layered tanka and those which give us pause for thought. This may give some insight into why I chose the poems I have.

The first is Mariko Kitakubo’s beautifully crafted tanka. I love her use of balance; balance of freedom and ‘isolation’, ending with ‘this Vernal Equinox Day’, the one day of the year where night and day are equal in length. Her ‘sky so blue’ tells me she’s happy (maybe with an important decision made?) and after the vernal equinox, as the days get longer, hopefully her happiness will also continue to grow.

The final poem I’d like to comment on is John Martell’s hard hitting stubborn cancer patient. I imagine the patient to be dying of lung cancer, with all the indignities it involves. Nevertheless he shuts himself indoors, smoking continually, ‘treating his tumours with contempt’ – his way of saying ‘do your worst’ to life and fate. This unexpected image provides a clever ending to an often cliched topic.

I feel that sharing something we’ve created, like tanka, demands a huge amount of trust, especially when we send our little creations, like children, out into the world. Thank you all for trusting us with your tanka. They were a joy to read!

L.M.Tesoriero

Max Ryan

an appraisal by Maria Steyn

Max Ryan’s tanka caught my attention with its gentle, understated exploration of human emotion. Most readers will have viewed a full moon rising over the ocean, a lake or river and will remember how perfect and breathtaking a scene it is. The narrator in this tanka is no exception, he is acutely aware of the beauty surrounding him and even the moon’s iridescent reflection across the ocean does not escape him. The splendour of the scene is poetically described in the first two lines where assonance slows the reader down and adds a melodious tone. We find ourselves dwelling on memories of similar scenes and some readers might even consider how the moon inspires curiosity and wonder, carries an air of mystery and can be seen as symbolic of love or unattainable beauty and wholeness. A strategically placed comma invites us to savour the view and linger awhile.out of the ocean

a full moon rising,

I turn away

from its silver path,

shield my unlit heart

Max Ryan

After this introduction the next two lines take the reader by surprise. Instead of being immersed in the beauty and atmosphere of the scene the narrator turns from the rising moon and its ‘silver path’. Any sailor would attest to the fact that the ocean as a body of water is a fickle force to be reckoned with, and in the same manner life can be viewed as a mystery carried along by forces beyond our control. Who would then refuse to experience the exhilaration offered by a few minutes of treading along an illuminated path of perfection? Why would anybody want to turn from an enticing ‘silver path’ with all its fairytale connotations? Once again punctuation creates a pause and leaves us with many questions to ponder.

In the final line the reason for the narrator’s response is revealed with the alluring image, ‘shield my unlit heart’. The heart, traditionally the seat of emotion, is compared to a candle or lamp that has not been lit and the quiet sadness of this image touches the reader. Everything is luminous and filled with beauty: the moon, the silver reflection across the water, but not the narrator’s heart.

There are various reasons why a person’s heart could be dark, the most obvious being the experience of sorrow, pain, loss or grief. Light and beauty can threaten sorrow because it will invariably accentuate the painful emotion the person might be trying to subdue. A person might also fear to ‘contaminate’ beauty with the darkness they are experiencing, or they may feel like turning away from what can be perceived as ‘false advertising: life is imperfect, yet the magnificence of this scene entices us to believe otherwise.

It is the restraint, graceful imagery and simplicity in which complex emotions are explored that enchanted me in this elegantly written tanka.

I would briefly like to highlight two other tanka, the first being John Martell’s ‘across the pond’:across the pond

sunset explodes in bronze

and green fir spires –

we stand hands together

free from the weight of words

John Martell

Once again a nature scene stops two people in their tracks to admire the glory of a setting sun. The spiritual overtones inherent in the use of ‘spires’ pull the poem towards a deeper level and the final two lines leave the reader in a reverent state of silence. Are the hands held together in prayer, or are the two people holding hands? This double meaning enhances the effect of the poem and the profound image in line five offers the reader a brief glimpse into the release experienced when beauty and closeness set us free from the burden of words, entrusting us to a sacred realm of wordless understanding.

Lastly, a few words on Linda Galloway’s ‘the neat line’:the neat line

of Puritan grave markers

in a fiery sun

the noise

of their forbidden dreams

Linda Galloway

This tanka brought a smile of recognition. We notice the ‘neat line’ and ‘grave markers’ instead of elaborate gravestones – no excess, not even in death. How spectacularly the fiery sun releases all those repressed desires and dreams!

Michael McClintock

an appraisal by Kirsty Kirkow

It is an enchanted moment when a poem leaps off the page springing into the reader's heart and mind to be remembered and repeated. This lightning link has much to do, I feel, with background, culture, interests, sensitivities and possibly recent reading material.

I had just finished enthusiastically re-reading Kidnapped and was in the midst of a novel about expatriate Scots in colonial America, the day that Eucalypt arrived in the mail. I opened the silken pages. Wham! There was McClintock's poem bellowing at me for attention. It is a strong, blatant verse; a surfeit for the senses.I have a Scottish background (Kirsty being a Gaelic name) and have all my life heard fabled stories about the haggis, a wee beastie that runs around a mountain, always in the same direction, with the uphill legs shorter than the downhill ones. The taste of it does not bear discussion. Believe me, a little goes a long way. Much the same can be said for bagpipes, an exciting wild wailing meant to scare the enemy but, again, a little goes a long way. McClintock may have visited the land of his forefathers hoping to connect and resonate with it, but five days were enough! His clan probably left Scotland for religious reasons but he found the culinary and musical persecution sufficient to make a man flee. Notice that the word bandit comes from the Italian bandito, from bandire, to banish. Interesting choice, no? They all felt banished.after five days

bagpipes and haggis aplenty

I'm going to flee

old Scotland, the same as

my bandit fathers before me

Michael McClintock

It appears that the poet longed to connect with his history; and he expresses an underlying disappointment that he was not captivated by it. Is there a conscious decision to cover this disappointment with wry humour, using some vocabulary resonant of the Old Scotland he had hoped to be part of?

There is musical rhythm despite a couple of pretty long lines for tanka. There is a narrative with a beginning and conclusion. There is a mid-poem pivot and a turn of image and subject in L5 that creates a strong final line; the realisation that a love affair with Scotland was not to be. For me, this is the epitome of a modern English tanka, redolent with classic Japanese undertones and a lot to admire.

In direct contrast to McClintock's rough and ready tanka is this one, by Jan Dean. A poem of meditative serenity that draws the reader irrevocably into its charmed circle. The quiet language shows how discursive thoughts can subside into the deep peace of a quiet mind. A Zen garden. The visitor is first attracted to the movement of the fish before realising the meaning and affect of sand and stones. This is a very powerful tanka, beautifully executed.

There is also the captivating carp drawn by Pim Sarti.on my first visit

I missed the raked garden –

today the stones

shift my mind further

than the carps' fluidity

Jan Dean

I cannot leave you without mentioning a poem by John Martell which startles the senses with almost violent imagery, the shock of which stuns its viewers into silence...and an understanding of the powerlessness of words in the face of natural events. Do not miss the implications of that one small word – spires. And, are they holding hands, or praying?across the pond

sunset explodes in bronze

and green fir spires

we stand hands together

free from the weight of words

John Martell

It is impossible, as you can see, to choose one poem from such a fine collection as is consistently presented to us in Eucalypt by its editor, Beverley George.

Carole MacRury

an appraisal by Max Ryan

When judging poetry of any kind it's always hard to decree one poem as better than all others.

Tessa Wooldridge’s seamless metaphor of a musical stave to depict the far west NSW network of fences and rail track touched on something powerful and unique to this country and I can imagine anyone who has ever lived in those regions or travelled the train-route from Parkes to Broken Hill would find deep resonances in this poem:from Ivanhoe

to the Menindee lakes

fence, train track, fence

a stave in musical harmony

singing across the land

Tessa Wooldridge

I loved the assonances of Barbara Fisher’s image of a snowbound landscape where she contrasts ‘the rough red road’ that is now, in the grip of winter, ‘silent and white’:how strange

to see tree ferns

bent with snow

and the rough red road

silent and white

Barbara Fisher

Joyce Christie’s poem about a quayside farewell with its sorrowful mood of dispersement stayed with me for a long time:How effective the use here of ‘forever’.wind blown

ribbons blow away . . .

a sea of faces

forever waving

on the quay

Joyce Christie

Finally, though, the death-side scenario of Carole MacRury’s tanka, with its desperate cadences of a life being held onto beyond reasonable hope, stood out:a glass vase filled

with out-of-season tulips

oh, how we tried

to force-feed spring

into her winter decline

Carole MacRury

One of the ways a poem can fall down is the presence of 'leaking', where an unnecessary word obtrudes or where the reader may be diverted by an extraneous detail. At first I wondered about it being a ‘glass’ vase but then realised that this detail too added to the sense of transparency in the poem where the impossible feat of trying to maintain a human life beyond its natural limits is blatantly exposed. The ‘out-of-season tulips’ (suggesting the artificiality of this highly cultivated variety of flower, aggressively colourful and bold in appearance) are seen as filling the vase, one imagines, to its very limit. The poem’s final two lines bring the chill realisation of the force that has been exerted in this struggle with the disturbing image of spring being ‘force-fed’ into the winter of the woman’s dying hours.

Perhaps the author could have added an even more urgent tone to poem by putting the active verb ‘tried’ into the present tense but the atmosphere of a fast-fading life is depicted so vividly here, we are left finally with the subsuming sense of hopelessness we all must feel in the face of death’s natural, inevitable unfolding.

Beatrice Yell

an appraisal by Michael McClintock

sky scraper cranes

above a building site

on the footpath

a heap of crisped, fallen leaves

beside a birch twig broom

Beatrice Yell

Occasionally, a tanka poet will step out of the self-reflecting mode and craft a poem that invites the reader to engage in a different level of contemplation, placing emphasis on idea rather than emotion.

The huge themes and ideas that Beatrice Yell has compacted into the matter-of-fact language and spare lines of her poem bring to mind those passages in Ecclesiastes that speak of a time for every purpose and for every work, and how under the sun all things are full of labor.

Embedded in the poem’s simple imagery is a powerful sense of human and natural history, the flux and flow of things, intertwining human activity with natural processes. We see in the construction crane about to swing into action, and in the rustic broom about to tend to its sweeping, the alpha and omega of beginnings and endings, a contemplation of man and his works within the great harmonies and cycles of nature: constructing and deconstructing, rising and falling, filling and emptying.

The mind that made the construction crane and harnessed the laws of physics also fashioned the lowly birch twig broom. One is a tool for building, the other a tool for sweeping away. In them, we see a large part of man’s activity on earth, generation-to-generation, all played out within earth’s own unceasing but mute natural cycles of growth, increase, and decay. In the mind’s eye, the scene evolves before us: the building rises beam-by-beam, piece-by-piece. In spring, as the building goes up, the bare trees along the footpath will leaf-out and once again a green summer will be provided its light and shade.

I think the poem is true to the complex realities of history and of contemporary life. It appears to be grounded in a pragmatic philosophy that sees man and nature bound up together in a relationship that is essentially complimentary rather than inherently or necessarily confrontational. There is no symbolic evil in the construction cranes; no romantic or sentimental fantasy about nature. It is a quiet poem of illumination, reflecting on the Big Picture, and is delivered sans rhetoric in the simple language of sincerity. I am persuaded that Ms. Yell must be a natural philosopher of the first order, and may be as wise as Solomon.

****

Elizabeth Howard

an appraisal by Beatrice Yell

institution child

boxers riddled with holes

shirts buttonless

where to start

to make amends

Elizabeth Howard

In the ninth edition of the excellent international tanka journal Eucalypt I found the superb quality of the poems on a vast range of themes impressive. As subscribers, we can read and ponder upon submissions from all parts of the globe. These vary from the immediacy of visual impact – such as Barbara Fisher’s plum blossom, and David Terelinck’s the stars, to Catherine Smith's bacon and eggs with its implied optimism. And from the empathy stirred by Joyce Christie’s dawn, Carole MacRury’s morning sun, the quirky ‘groundhog day’ scenario of Jo McInerney’s I run so hard and the suggestive reminiscence of Bob Lucky’s just as I am – to the one that seared me to the core – institution child by Elizabeth Howard.

This poem’s first three lines state simple facts in matter of fact language. This leaves the reader faced with a practical and manageable task; the repair and replacement of clothing for the institution child. Then it changes to the personal; where to start. A quick shop at a chain store as well as a little time with a needle and thread and a packet of buttons can only do the visible mending. But as for the rest of the mending – it is indeed a quandary of mammoth proportions.

This particular child is likely to be one of thousands and even millions in a similar situation either in Australia, America, or in any part of our war-torn planet. That he is not given a name highlights and emphasises both his helplessness and his vulnerability. To even begin to address the incredibly difficult task of mending the anonymous child’s emotional wounds is a daunting task.

Here, the skilful use of the word ‘amends’ has been used to pinpoint this dilemma and works well allied with the suggestion of the physical act of mending in this poem. The use of straightforward, unambiguous language in this tanka heightens every word to resonate within this reader.

Even just one child in this situation is one too many. Long-term studies reveal the catastrophic impact of abandonment on babies and young children, from birth onwards. Such waifs will face the same challenges as other children, without the confidence and identity which strong family bonds provide. Little wonder they grow up troubled in a troubling world.

A simple tanka has the power to inform and engage the reader concerning topical global issues that impact on us all.

Sonam Chhoki

an appraisal by Carole MacRury

It was a great pleasure to have the honor of choosing one distinctive poem from among all the superb poems we consistently find in Eucalypt. The process was made easier for me once I realized this task was less about judging one poem against another and more about my own personal taste and sense of connection. As I read through the journal once, twice, taking notes on poems, I realized my selections were geared to my mood and the circumstances of my life at the moment. I found myself drawn to poems which I felt had an authentic voice. To poems that took me by surprise, swept me into an intense feeling of simpatico for another poet’s experience and mindset. This strong connection was often enhanced through the use of sensory and figurative language, strong images, alliteration, metaphor and other such poetic devices. The following poem is the one that I consistently came back to, gaining something more from it with each reading and which I finally selected for the Distinctive Scribbling Award.new year dusk –

two black figures on the bridge

are old wooden posts

what else have I mistaken

in the year just closed?

Sonam Chhoki

I was surprised not once, but three times in reading through Sonam Chhoki’s poem. The first time was in the dim setting of the opening line. A new year suggests new beginnings to many, a clean slate, a new start, a new day, but this poem opens a new year at dusk, reminding us of the year just closed. The poem darkens even more with the observation of two black figures on a bridge, a deeply resonating image. I found myself peering intently into the scene right along with the poet, even to the point of squinting, wanting to reach for my glasses for a better view. The second surprise comes like a magician’s sleight of hand with the discovery that what seemed real was but an illusion, a trick of the mind. The correlation between the first three lines and the final two lines comes as an epiphany in that one suddenly wonders what other things in the past year were not as they seemed. What else may have been misinterpreted or in some way not seen clearly and truly. The sense of speculation in the final two lines was further enhanced by the assonance of ‘posts’ and ‘closed’ effectively bringing the two parts of the poem together.

I would also like to offer honorable mention to the following poems and their authors: “winter sunshine” by Julie Thorndyke, tickled my senses with the spreading warmth of the sun as lover. Naomi Beth Wakan’s “tidal pool”, for the voyeuristic experience of watching barnacles “kick open” to feed, an intimate action that resonated with the feeling of “welcome” in the last line. Kozue Uzawa for what I felt as a startling epiphany in “picking pumpkin seeds” and the way she left space for the reader to contemplate life after the wedding. John Soule’s sense of aloneness with “alone on the patio” where even the mosquitoes are not interested in taking a bite and Beverly Acuff Momoi for “our tortoiseshell cat” in which she uses form to enhance the cat’s action with alliteration, “fierce focus” and parallelism, “belly chest shoulders/mine mine mine”.

Mariko Kitakubo

an appraisal by Sonam Chhoki

I felt like Roald Dahl's Charlie in the Chocolate Factory. As I saw it, Eucalypt is a poetical phantasmagoria, where tanka adepts from around the world display imagination, skill and technique to articulate their deepest emotions, thoughts and experiences. With this came, to paraphrase George Steiner (No Passion Spent), 'a nagging weight of omission:'

Which tanka should I pick from among the impressive array? Would I do it full justice? What if I omit a worthy tanka?

It did not altogether diminish the delight with which I revisited the poems several times. This tanka by Mariko Kitakubo began to grow on me. It has a compaction of imagery and allusions (personal, mythic, poetical) that played on the mind each time I read it.

moonlit night

in the bamboo forest

a child god

transforms into a badger

to summon his mother

The seemingly straightforward description in the first two lines of the tanka:

moonlit night

in the bamboo forest

takes on a certain charge with the line:

a child god

The reader is forced to stop and take note. It evokes for me allusions of myths and beliefs – deities appearing to the initiated, the innate sacredness of nature and the allusion to the archetypal magical attributes of the moon itself. Even as the reader holds their breath there is shift and a metamorphosis of image and perception. The child god (divine) transmutes into a young badger (mortal). The line:

to summon his mother

suggests a vulnerability of the badger cub and there is a note of tenderness in the poet’s observation. What struck me is the immersion in the scene and moment that Mariko Kitakubo creates with a deftness and lightness of touch while remaining an unobtrusive observer.

An arresting detail of this tanka is the way the shadows of the bamboo in the light of the moon mirror the stippling black and white effect of the badger’s head. It evokes a poetical parallel with Blake’s Tyger, whose golden and black stripes are described as ‘burning’ in the ‘forest of the night.’

The tanka has a pleasing sonority when read out aloud. The long ‘o’s in moon and bamboo and again the recurring ‘o’s in forest, god, transforms, summon and mother slow down the pace and create a sense of wonder as in an echoing Oh! The near-rhymes of mother and badger as well as in the short ‘it’ in lit and long ‘it ‘in night further enhance the sonority of the tanka.

Mariko Kitakubo’s tanka is imbued with a sense of a magical moment and as a reader I felt privileged and moved to be allowed to share this.

It would be remiss of me to neglect other tanka in this issue, which deserve a very honourable mention.

Ian Storr’s tanka is very Vermeer-like in its portrayal of light, shadow and above all, translucency– the turquoise blue, one imagines, of the settled sea, the light on the balcony reflected by the white plate and the suggestions of shadow mingled with transparency in these two lines create a veiling effect with a delicious sensuous overtone:

grapes the green of jade

the seeds within like shadows

John Quinnett’s tanka is also visually powerful. The repetitiveness of the falling leaves mirrors the repetitiveness of the woman’s sweeping. The slow-dance effect transforms a practical task into an aesthetical moment.

The ellipsis in Carla Sari’s tanka is laden with such poignancy:

‘We’ll meet again,’

I lie . . . to my sister

Another haunting tanka is by Linda Galloway:

am I still a mother

now that my child has died

echo the descent of the stone to an unfathomable depth.

Barbara Fisher’s tanka imbues a mundane daily chore, ironing with a poetical elegance. The quiet of the room is enhanced by the lengthening shadows and the contrast with the hiss of the iron steam sets up a contemplative tone. One gets a sense of an instance all the more precious for the unexpectedness of it – a kind of finding the sacred in the profane.

I also like the child-like delight that Mary Franklin captures in her tanka. The assonance in again, train and rain brings out the sense of a gush of inspiration.

Athena Zaknic’s tanka conjures a sinister setting – dusk, her slow walk from the bus stop, his waiting underlined by the line:

now on his fourth stubby

There is a back-story to this and an uneasy sense of something about to happen, which raise questions:

Is he a stalker? Is he a violent parent or partner?

That the poet offers no answers makes the tanka all the more compelling.

Finally, Max Ryan’s tanka has a brooding sense of mortality:

… sixtieth birthday …

the darkness out there

… the tug of an unseen tide.

Sonam Chhoki

an appraisal by Elizabeth Howard

back home

from the oncology ward

I peel my first orange

the burst of juice and smell

colour of the sun I missed

Sonam Chhoki

I am impressed at the quality of the work in the tenth edition of the tanka journal, Eucalypt. The task of choosing one tanka over all of others is rather overwhelming. Two tanka about writing, Shona Bridge’s a distant light and Mary Franklin’s suddenly, appeal to me as a writer who knows about the two pages, one blank, the other overflowing with words that pour from some source beyond us. I am intrigued by Kath Abela Wilson’s when what might happen/happens, sympathize with the ones who have experienced recent earthquakes: Barbara Strang, Helen Yong, and Nola Borrell. None of us are immune to natural disasters—floods, tornados, hurricanes, fires, etc., that shatter lives. Other tanka appeal to me: Michele L. Harvey’s painting, Allegria Imperial’s into fog, Lynette Arden’s thanks to my mother, Max Ryan’s woken on the eve. One that I like especially well–that I also wanted to choose–is Edith Bartholomeusz’s tanka about children. Far too many children in all parts of this earth are on the far side/of the river:–/no bridge/from there to here.

After reading through the tanka several times, I eventually chose back home. This tanka followed me around while I was making up the bed and doing laundry. Chhoki has captured the universal experience of cancer and chemotherapy in a wonderfully positive way. We all know the horrors, either through personal experience (I have had breast cancer) or the helpless agony of watching a loved one or a close friend suffer and deteriorate (I have lost a daughter and a sister). Chhoki has hinted at the months of treatment, but chosen to emphasize the joy of recovery.

She leaves the misery, the darkness, colour of the sun I missed, to the end of the poem, after we know the story has a happy ending. When the doctor pronounces the sentence, perhaps avoiding eye contact, the lights go out, the sun hides its face. The world is gray, foggy, dreary. Favorite foods lose their flavor, become repulsive; the morning coffee tastes like metal. The smell of food, bubbling on the stove, baking in the oven, roasting on the grill, is nauseating. Hair falls out, skin becomes ashen. The face in the mirror is ghostly, skeletal. Exhaustion begins the day and ends it. Walking, even a few steps, causes faintness. The mind is clouded. A simple chore, such as balancing a checkbook, the household accounts, is a long arduous task.

The first line, back home, is wonderful. Home is that comfort place we hurry to after a long arduous journey or a hard day’s work. There we can kick off our shoes, put on our old faded jeans, breathe deeply, and relax. There we refresh mind, body, and spirit for a new beginning. In the second line, we learn the long arduous journey has been to the oncology ward, sitting for hours while poisons drip into the vein, poisons that cause such awful nausea, fatigue, depression. All of that is past now, we are home.

Color bursts back into our lives, into our faces, senses reawaken. Once favorite foods again become favorites. We rejoice in the smell of bread baking in the oven. Morning coffee has the aroma, the taste, that we love, that sets us stirring, ready for sunrise, birdsong, a walk among the flowers. Walk, such a wonderful word. What joy, that first hike, actually climbing a hill after many months of incapacity. The mind is whole again. Thoughts, dreams, ideas burst forth as juice bursts from the orange. All of the lights that were extinguished back there in the oncology ward are back on again. We soak up the sun, a giant orange ball rising in the east, in a radiant halo of color, colors we know and colors so rare we do not even know their names.

Joy to all who have traveled through the darkness and come back home to the light.

Elizabeth Howard

David Terelinck

an appraisal by Mariko Kitakubo

only the moon

understands my grief . . .

waxing, waning

sometimes so complete

it cannot be ignored

David Terelinck

From my first reading of this tanka, I could feel the silence, beauty and coldness of the moon.

The moon has changing faces . . . new moon, crescent, half moon, full moon . . . and as you know, we are usually unable to see it by day.

And I often feel that the moon is watching over me – like my late parents.

While I can't feel the strength or dazzle of the sun from the moon, the moon has particular nuance, I think.

The poet, David Terelinck, also feels the healing from the moon. He wrote "only the moon understands my grief . . ."

I immediately felt drawn toward the first 2 lines. "my grief" is the writer's own emotion at first, but then we (the readers) can share his emotion as our own.

He expressed this directly by the beginning word, "only". We can understand about the writer's solitude and that no one could understand his grief but the moon.

And he continues to consider the phases of the moon. "waxing, waning"; "...so complete" These also relate to our life, our feelings and passions.

He used the word "sometimes" . . . yes, sometimes our life appears to be "waxing " and "so complete". But also sometimes "waning".

In the depth of my difficulties, I feel this "waning" of myself.

But we are not alone, I think . . .

The Moon is watching me, watching us, like our best friend, like our late parents or late grand parents.

Are they smiling in your hearts?

Yes, they are always smiling in our hearts and watching us, sending their deep love.

In the last line, he wrote, "it cannot be ignored".

Yes, like our beauty of our own life, we can't ignore the beauty of the complete moon.

This tanka expresses our common feeling of life perfectly by the poet’s excellent skill.

David Terelinck, thank you so much for sharing this wonderful tanka.

Rodney Williams

an appraisal by Sonam Chhoki

While in the creative throes of composing Kubla Khan, Coleridge was famously interrupted by a visitor from Porlock. In my case the visitor from Porlock took the guise of indecision. Which one from the many accomplished tanka should I pick?

Then I had a dream. It was the New Year pilgrimage to the cave temple, high above my ancestral valley. People were prostrating and offering fruits, butter lamps and coins. I held out the Eucalypt Issue 11. The eyes of the Buddha of Compassion opened. But before he could speak I woke up.

The visitor from Porlock was still in the room. I read the poems all over again and this one by Rodney Williams began to take shape in my mind.

in a field

flanked by plum trees

a chimney

its wood-fire stove

burning with rust

The imagery of a field flanked by plum trees immediately opens up a vista. The tanka then turns with an unexpected image of a chimney. The juxtaposition of the field and plum trees on the one hand, and the chimney and the wood-fire stove, on the other, evokes a surreal de Chirico-like effect.

The verb:

flanked

has a military ring to it, suggesting order in the way the plum trees stand, and contrasts with the solitary chimney of the abandoned wood-fire stove.

Williams’ tanka is one of dichotomy of nature and civilisation. The discarded stove represents the latter. The detail:

burning with rust

hints of the colours of autumn while the plum trees are a classic symbol of spring particularly in Japanese poetry. There’s a sense of the triumph of the natural world over that of civilization in that the plum trees and the field are still alive and can renew themselves, whereas the man-made artefact, the wood stove, which used to burn wood, is now defunct.

Williams has imbued a moment of keen observation with a potential for a more universal awareness of the nature of things. The power of this tanka lies in the way it suggests multiple reading of a relatively simple scene.

Other poems too have made a deep impact on this indecisive reviewer and deserve a special mention.

Barbara Strang has an unexpected framing of the mountains in this detail in her tanka:

through metal struts

the flawless mountains

Regret and anguish are captured in these lines of Barbara Taylor's tanka:

... does it really matter

mother never knew?

Louise McIvor's tanka has a similar poignant note:

our rose bush

finally in bloom

Peggy Heinrich's tanka carries the weight of childhood guilt and loneliness.

A poignant sense of being out of sync with the world around them, come across in the tanka of both Amelia Fielden and Joyce S Greene. Fielden's:

a mind too aware

of what comes after dawn

is laden with disquiet and Greene's detail housebound marks a painful rupture from the world outside.

Ken Moore's keen observation of a toddler's silent plea is imbued with a note of compassion.

There is skilful combination of metaphor and physical description in Carole MacRury's tanka:

offstage ...

rinsing the rage

from his painted face

The alliteration in rinsing the rage has an onomatopoeic effect.

Mary Franklin's tanka likewise observes a shift, the green hat denoting a rather positive and creative outcome.

I like the sonority in Kirsten Cliff's

tinker, tinker tinker

of teaspoon against mug

and her motif strikes a chord with many of us who have struggled with editing our poems.

There's an irreverent note in the old woman's laugh drowning the ring of a much coveted and iconic contemporary gadget, the iphone. This makes Alex Ask's tanka a delightful read.

Finally, I would like to conclude with J. Zimmerman's celebration of enduring love:

thirty years later

... the grasp still strong

Dorothy McLaughlin

an appraisal by David Terelinck

Beverley George’s keen eye for high quality tanka ensures that every poem in issue 12 of Eucalypt is worthy of a Scribble Award or special mention. In doing so, Beverley ensures each person who has to pass the Award to a new recipient has an extremely difficult challenge in front of them. There are many exceptional tanka in Eucalypt issue 12 that are more than worthy of the Award. And these all appeared vividly on each subsequent reading of the journal. However, the one poem that kept drawing me back over and over was Dorothy McLaughlin’s tanka on page 7:prayersFor someone who is a lover of classical tanka, I felt this poem has it all . . . the classic structure of S/L/S/L/L format, no redundant words or phrases, and is a tanka where each line successively builds on the strength of the one before it to create a tanka that touches the heart, soul and mind. It is a tanka not easily forgotten, and has many subtle layers.

at their child’s deathbed –

the answer

that left his faith stronger

made her an atheist

Dorothy McLaughlin

For me this tanka encapsulates three of the themes that classical Japanese tanka poets wrote about; it contains all the elements of love, loss and longing. Who could not be moved by the plight of devoted and loving parents praying at the side of their dying child? The love of parent for child is said to be one of the strongest and most motivational loves within the world.

And this very act of prayer and love at the deathbed gives such a visually strong image of the imminent loss they must prepare for. But beyond this physical loss of young life is also a loss of relationship; for we inherently know that husband and wife must drift apart if the poles of their faith are moving in vastly opposing directions. And then we see a spiritual loss for the wife . . . the death of her child, and a failure of prayer to be answered, “made her an atheist”. This careful selection of phrase suggests this wife was not an atheist before this event, and therefore there is an acute loss of relationship with her faith.

There is a desperate sense of longing evident within this poem. Longing for the prayers to be answered, longing for their child to live, perhaps the one with faith longs for a peaceful passing of their child, or from the other a longing to have a faith that sustains. One can also imagine a longing that many parents may experience in similar situations . . . that roles were reversed with them and their child.

The tanka opens with an expansive view due to the use of a single word of great strength, prayers. Prayers are open to everyone who chooses to use them, and can encompass an unending scope of requests from the insignificant to the profound. This gives every reader an entry point that pulls us immediately into the tanka; we all have the ability to pray. This view then very quickly narrows in line two as we are directed to the reason for the prayers – a dying child. The tanka again opens up in the last two lines to give us so much space that whole worlds now exist between the two parents. And this concept of faith and atheism ensures we are taken back to our starting point of prayers. In this manner the tanka has a sensitive elliptical quality that is highly satisfying to the reader.

On each reading I continue to find something new in this tanka to enjoy. And although this tanka leaves me breathless with its pain and raw emotion, it does so gently, without hubris or intrusion, without preaching or proselytising. This tanka continues to linger at each reading, and will remain a firm favourite with me for many years to come.

Many other tanka within this issue also deserve a special mention. Each of the following has moved me for different reasons. But what they all have in common is a genuine poetic lyricism that never fails to engage me, a sense of relationship within the tanka that I can easily relate to, a gentleness of thought and expression, and a sincerity of emotion of the lived journey.

oversewing

heather with wattle

I tack on

the soft tread of your feet,

your arm linked through mine

Kathy Kituai (page 26)

I can see no one

for miles on these wind-roamed moors

yet, these breaths

of incense, secondhand . . .

another’s rite, or refuge

Claire Everett (page 28)

blue mussels

bubble through shells

half open . . .

like dying, this wait

for an incoming tide

Carole MacRury (page 40)

if you were here

we’d take our tea

up on the roof

and set the world to right –

if only you were here

Anne Benjamin (page 41)

Congratulations to everyone in issue #12. It has been a joy to read everyone’s work, and it is a sincere privilege to pass the Award to Dorothy.

Aubrie Cox

an appraisal by Rodney Williams

newsTwo people meet, over drinks, to chat. One of them is anxious to pass on news that seems personally devastating at first, only to take on other implications instead. In a further twist, such tidings provoke reactions from the listener which the bearer of bad news might never have anticipated ...

you’ve been dying

to share –

ice rearranges

in my glass

Aubrie Cox

It would seem that the two characters featured in Aubrie Cox’s intriguing tanka enjoy a long-standing bond. Gender is not specified - nor is the exact status of their relationship. Probably friends, and most likely both female, they would appear not to have seen each other recently.

At first instance, the opening of “news” suggests that the poem’s speaker – whether Aubrie herself, or a constructed persona – is hearing grievous tidings, to the effect that the friend has just been diagnosed with a terminal illness: “news/ you’ve been dying”.

Instantly, however, that bleak possibility is given a lighter spin, via a clever and playful use of enjambment spanning into the third line, combined with a colloquial – as against literal – turn of phrase. Rather than being at death’s door, the bearer of news might have gossip about others – or a personal disclosure – which she (or he) is “dying/ to share”.

A genuine strength in so sparse yet rich a piece is the way in which this tanka invites us to hypothesise. One reading could involve this pair sharing a third acquaintance, with the first character desperate to convey sensational tidings – hot off the grapevine – about unfortunate developments in the life of that mutual friend. Such information is grim, prompting – at first reading – a feeling of sadness, as symbolised by “ice”: plainly a sense of coldness imbues the second stage of this tanka. Yet perhaps the deeper scenario being suggested might not be – once again – quite as simple as it initially appeared.

Maybe this chilliness denotes not so much sorrow in itself, as distaste at having been told devastating news in an insensitive way. This iciness of heart could be directed towards “you” – the teller of sad tales – as an embittered response to hurtful gossip. To look at this possibility from a different slant, we could identify a further complexity in this apparently simple poem by appreciating its symbolism, not only on an emotional level, but also on a perceptual one:

ice rearrangesAcross this tanka’s punctuated break, Aubrie Cox effects an adroit transition: implicit here – in so few words – is a good deal more than the notion that the news conveyed has had a chilling impact, as characterised by a traditional (indeed, oft-used) metaphor of ice.

in my glass

We know that different types of lenses bend rays of light to varying extents, affecting what and how the human eye can see as a result. In a poem so spare in detail, the writer has opted to be explicit about the presence of not one but two substances that both have translucent, refracting properties: glass as well as ice.

The curved surface of a whisky tumbler is sure to distort beams of light, as will blocks of ice. Aubrie Cox pointedly shows how these ice-blocks shift about in their glass, rather than remaining still. Yet the poet is firm in her refusal to use a passive voice: she does not say that “ice is rearranged”. So frugal in its diction as to feel no need to say “ice rearranges itself”, the writing suggests that frozen blocks have not so much been jiggled around by the drinker’s hand, as they have become active – even reactive – of their own accord.

When ice-cubes move, the rays of light passing through them will be refracted differently. Again, if sorrowful news is conveyed too cheerily, this could likewise prompt an unexpected reaction – indeed, a new angle; a reassessment – in the form of distaste at insensitivity.